The Appeal of Flexible Capital Solutions

Flexible capital offers an attractive solution for companies and investors alike—and expands the universe of solutions across private debt and private equity.

Key Takeaways

- Companies always need capital. But depending on their needs and the economic environment, they are increasingly seeking new types of solutions.

- Flexible capital solutions span the middle ground between debt and equity and can be customized to meet a company’s specific needs.

- For investors, these opportunities combine the essential elements of both debt and equity in a hybrid, tailored investment structure with a focus on strong downside mitigation, along with upside potential tied to equity performance.

A Solution for All Cycles

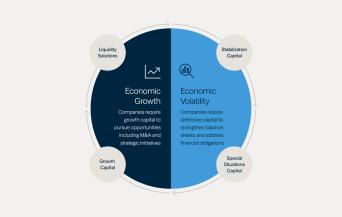

Markets and economies move up and down. But no matter where they are in the cycle, companies will always need capital—whether it’s to spur growth, shore up their defenses or access liquidity to support their corporate initiatives (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Flexible Solutions Across Economic Cycles

Flexible capital is a global, all-weather solution that sits between traditional private credit and traditional private equity. The key is customization: A company teams up with a strategic partner who provides alternative sources of capital to help execute its vision.

For investors, it combines the essential elements of both debt and equity in a hybrid, tailored investment structure with a focus on strong downside mitigation, along with upside potential tied to equity performance.

More Companies Are Turning to Alternative Solutions

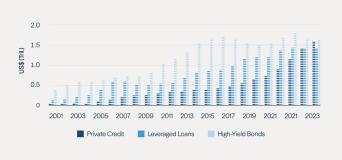

Since the Global Financial Crisis, it has been more difficult for companies to access traditional forms of capital. Private markets increasingly have filled the void. The U.S. private credit market, for example, reached $1.7 trillion in 2023, comparable to the U.S. leveraged loan and high yield markets (see Figure 2).1 In 2025, private credit is estimated to total about $2 trillion globally, though one estimate placed the market closer to $3 trillion.2

Figure 2: The U.S. Private Credit Market Is Gaining Ground

Source: IMF

Companies can also turn to the private equity markets, but doing so means that the management team would need to dilute its equity ownership of the business. Not to mention that the cost of capital tends to be more expensive, especially if the market timing means that management needs to issue equity well below the company's intrinsic value.

In this financing environment, flexible capital solutions have emerged as a strong alternative for companies with specific needs.

Finding a Middle Ground Between Debt and Equity

Structured capital solutions span the middle ground between debt and equity (see Figure 3). And because they are customized through a negotiation process, each structured capital solution is unique.

Figure 3: Solutions Along the Debt-to-Equity Spectrum

A more debt-like instrument, such as preferred stock plus warrants, can be used to right-size a company’s leverage, while giving the capital provider downside mitigation over other equity owners.

This downside mitigation is based on the risk level of the provider’s capital—in other words, a higher position in the capital stack. For example, if the capital provider’s last-dollar loan-to-value ratio is 60% of a company’s total enterprise value, 40% of the value could erode from that business, but the capital provider would still get its last dollar out.

In a debt-like investment, most of the capital provider’s return comes from consistent preferred equity dividends, which tend to be higher than those for a more equity-like structured instrument. Meanwhile, the warrants offer some additional upside to the underlying preferred return if the long-term equity story for that business plays out.

This type of debt investment often saves the capital provider and the target company from having to agree on a valuation for the business. This helps facilitate transactions where valuation expectations between the two parties are not aligned.

Alternatively, a capital provider investing in a more equity-like instrument, like a convertible preferred, inherently believes that the underlying equity value of a business will grow materially over the long term. This equity-like investment would have a lower running cost of capital but would generate a higher amount of the overall return from the equity component.

This allows the capital provider to support the company’s growth strategy while participating in its share of the business’s profitability. These types of solutions tend to work well for a misunderstood, dislocated business, where the capital provider and the counterparty roughly agree on where the valuation lives. In other words, structured capital can reduce the market timing risk found in traditional private equity by offering a premium valuation in exchange for downside mitigation.

The Opportunity Set Is Wide

Today, structured capital solutions are essentially another capital source for both public and private companies to choose from. But importantly, they are more flexible than other options. They can:

- Maximize flexibility within a capital structure—and stabilize or repair a company’s balance sheet

- Provide growth capital to support a large strategic acquisition or a roll-up type acquisition strategy, or to provide development capital

- Supply access to capital, especially where “blunt” instruments, like high yield bonds, leveraged loans or equity issuance, might not be the best option

- Limit the cost of capital and dilution for public companies that want to grow or acquire other businesses, but don’t want to take on more debt or issue more common equity

- Allow a company to gain a strategic partner—who can assist with operations, acquisitions, capital markets, etc.—while still maintaining control

As a result, structured capital solutions appeal to a wide variety of companies. These can include private, founder- or management-owned businesses that want to maintain control and ownership of the business along with the potential upside, private-equity-backed companies where the sponsor is looking for access to incremental capital, and more.

Providing Meaningful Capital—With Protective Features

Flexible capital offers an attractive solution for companies and investors alike—and expands the universe of solutions across private credit and private equity.

Companies today are looking for meaningful capital and partnership, without having to take on more debt or dilute their equity ownership. As corporate boards and management teams become more sophisticated and comfortable with assessing possible financing options, more are seeking out new types of solutions.

For the investor, flexible and strategic capital solutions cover an attractive middle ground between debt and equity. Since part or all of the return is contractual, these investments can include downside protection with more upside exposure than traditional debt. And since these transactions are often highly negotiated, the inclusion of other protective features—like board seats or consent rights—only enhances the appeal of the asset class to investors. Capital providers can assist in influencing a company’s overall strategy without taking full control—and help drive great outcomes.

Endnotes

1. U.S. Federal Reserve, “Private Credit: Characteristics and Risks,” February 23, 2024. The Fed cites Preqin for data on private credit.

2. McKinsey & Company, “The next era of private credit,” September 24, 2024; EY, Alternative Investment Management Association, “Financing the Economy: The Future of Private Credit.”

Disclosures

This commentary and the information contained herein are for educational and informational purposes only and do not constitute, and should not be construed as, an offer to sell, or a solicitation of an offer to buy, any securities or related financial instruments. This commentary discusses broad market, industry or sector trends, or other general economic or market conditions. It is not intended to provide an overview of the terms applicable to any products sponsored by Brookfield Asset Management Ltd. and its affiliates (together, "Brookfield").

This commentary contains information and views as of the date indicated and such information and views are subject to change without notice. Certain of the information provided herein has been prepared based on Brookfield's internal research and certain information is based on various assumptions made by Brookfield, any of which may prove to be incorrect. Brookfield may have not verified (and disclaims any obligation to verify) the accuracy or completeness of any information included herein including information that has been provided by third parties and you cannot rely on Brookfield as having verified such information. The information provided herein reflects Brookfield's perspectives and beliefs.

Investors should consult with their advisors prior to making an investment in any fund or program, including a Brookfield-sponsored fund or program.